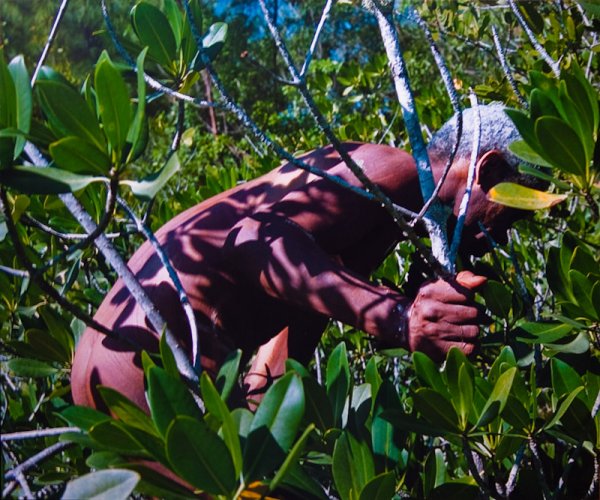

“Mangrove, Mud, Mystery (series)”

performance action part #1a

“Mangrove, Mud, Mystery (series)”

performance action part #1b

“Mangrove, Mud, Mystery (series)”

performance action part #2b

Lambda print on gatorboard

24 x 30 in.

During the working of project, “Water is the Barrier” there was a dream sequence of a lone male figure actively participating in the landscape (where I was working to photograph “Water is the Barrier,” here and here.) I saw this figure walking thru the mangroves and scrub without regard to time and place. This image stayed with me for six years when I had to opportunity to recreate this dream. I collaborated with friend, Dan Norton, photographer, to create this series.

Though performance art was not something I actively sought out, it has become an integral part of my art practice.

Mangroves in Florida mark the boundaries of land and sea. They form a unique ecosystem around bays and estuaries and are one of the primary ingredients in the life and food chains that begin there. They provide habitat for a variety of coastal organisms both in and out of the water. Many times mangrove thickets provide a perfect sanctuary for birds seeking to safeguard their nests from raccoons and snakes, and so mangrove islands many times are rookeries.

The mangrove forest as a mesh of both land and water, and its fluidity and borderless, is open to influence and change. Yet because of its rhizomatic lateral growth patterns, which prominently feature prop roots and pneumatophores, it can also contain, entangle, strangle, and bind, and thus act much like a natural barrier.

It is precisely this constant flow, the intake and uptake of nutrients, excretion, — that is, the biological activity — that makes the mangrove one of the most vital, successful of all ecosystems, and thus an excellent metaphor and model for our dualistic society.

The mangrove forest would of course have offered a familiar terrain to those slaves brought from coastal West Africa. While infamous for its impenetrable maze and still considered by some as “a wasteland of little or no value,” the mangrove is in fact highly valued by natural scientists for its hardiness and great adaptability to the physical stresses on the system as well as for offering stability and protection to island and coastal regions against erosion and storm damage, among other benefits. These plants have developed physiologically and morphologically in order to survive environments of high salinity, occasional harsh weather, and poor soils.

One of the most visible adaptations by mangroves is their prop roots and pneumataphores, obviously the physical characteristics that tie them to the Deleuze and Guattari paradigm. But as the two scholars also suggest, border zones are sites of creation and challenge. They remind us that the so-called postmodern world has altered in many ways and places what was assumed to be a “seamless join” between place and identity.

As Deleuze and Guattari emphasize, the rhizomatic is not amenable to a structural model, and is a map rather than a tracing: “To be rhizomorphous is to produce stems and filaments that seem to be roots, or better yet connect with them by penetrating the trunk, but put them to strange new uses” (A Thousand Plateaus). Deleuze and Guattari tell us in theoretical studies that there is a need for looking beyond roots.

Comments are closed.